Select Language:

PUBLISHED

November 23, 2025

KARACHI:

Pakistan begins each new fiscal year with a familiar uneasy mix of hope and fatigue. Inflation continues to disrupt households, foreign reserves fluctuate unpredictably, and government officials speak of recovery in terms that feel more like mere survival than genuine growth. Across offices in Karachi and Lahore, young engineers search for job opportunities that are often scarce, while factories in Faisalabad operate below capacity. The nation is still trying to regain its footing after years of instability, all while striving not to fall behind in a swiftly digitalizing world.

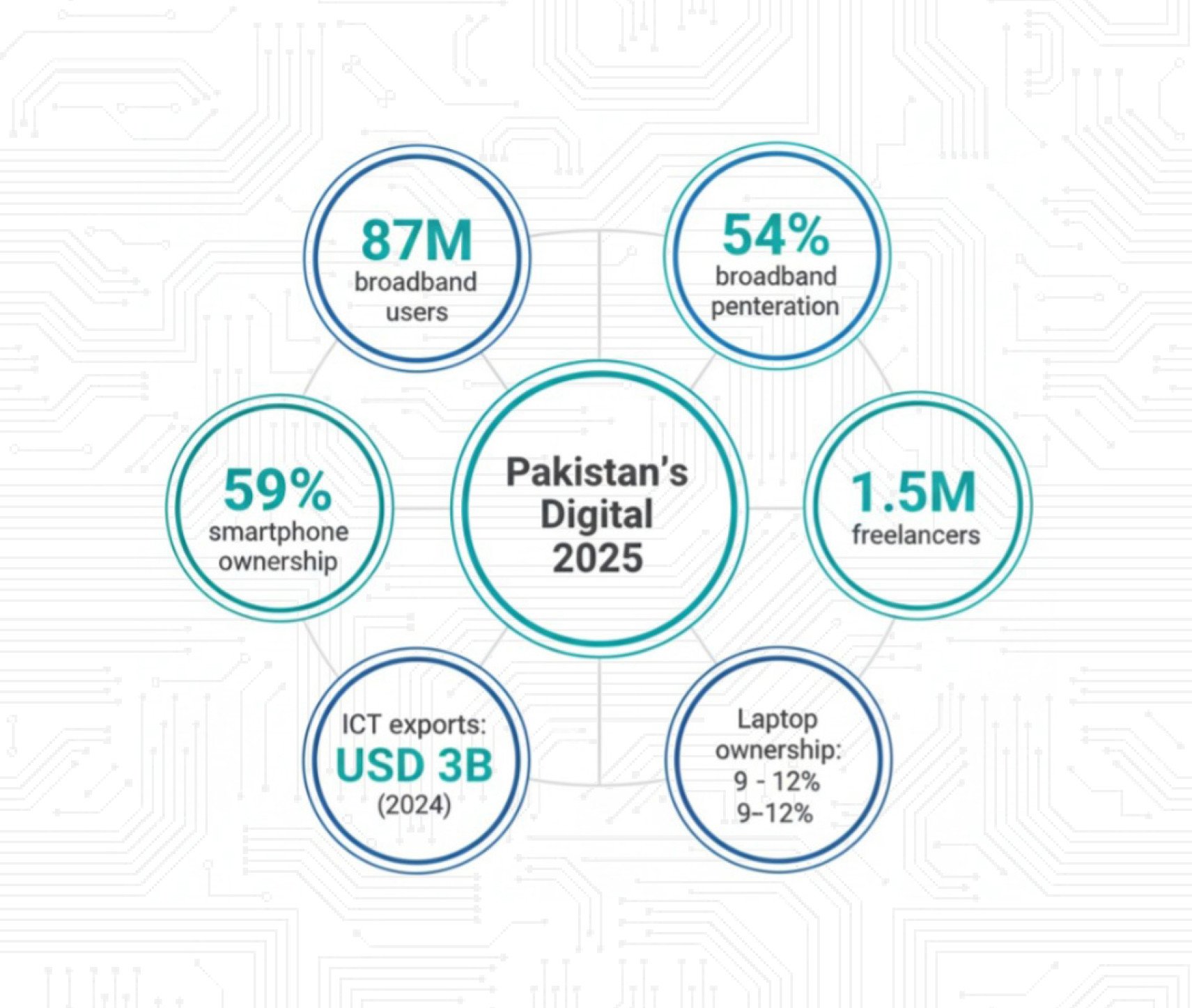

On one hand, Pakistan’s tech industry offers a rare sliver of optimism. Freelance workers have quietly established the country as a notable hub for remote work globally. Software exports have surpassed three billion dollars annually. While startups faced funding shortages that slowed their growth, they still foster innovation in logistics, financial technology, and e-commerce. Conversely, the country remains heavily reliant on imported hardware—laptops, desktops, tablets, servers, even computers for schools—which continue arriving at costs the economy finds difficult to bear.

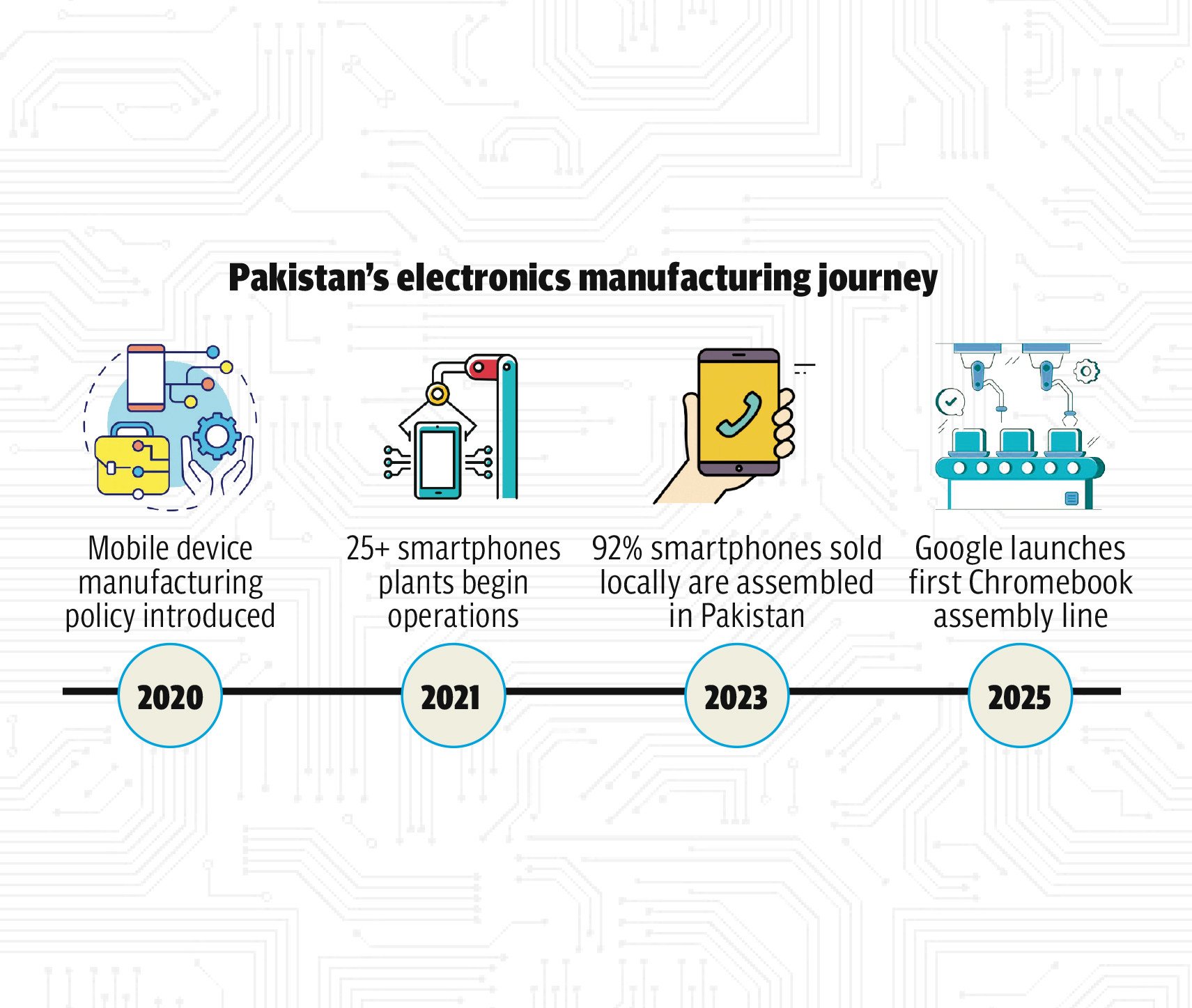

At the same time, international tech companies are cautious about entering Pakistani manufacturing. Brands like Samsung, Xiaomi, Tecno, Vivo, and Infinix have set up assembly plants, and longstanding appliance brands such as Haier and Dawlance are entrenched here. Over 25 smartphone manufacturers now operate domestically, localizing up to 90% of devices sold in the market. However, beyond mobiles and household appliances, Pakistan has rarely been seen as a viable location for global hardware companies to establish long-term manufacturing bases.

Therefore, when a new assembly line opens for any technology category—especially computing—it carries weight beyond just the device being produced. Even basic assembly can gradually shift local capabilities by creating technical roles, integrating global processes, expanding supplier networks, and providing governments with a reason to emphasize industrial policy. For an economy seeking stability, these are meaningful changes.

Within this context, Google has taken a significant step that Pakistan has been anticipating. Earlier this month, the company announced the launch of its first Chromebook assembly facility in Haripur. The units are simple, cloud-centric laptops assembled through a partnership involving Google, Tech Valley, Allied, and NRTC. While these are basic devices, the move signifies something larger—an entry of a global tech giant into Pakistan’s traditionally underdeveloped industrial landscape.

What unfolds next, and how Pakistan leverages this moment, could influence the country’s digital trajectory far more than the devices produced today.

A modest start with big implications

For years, Pakistan has discussed shifting from a passive consumer of global technology to a player that produces at least some of that technology locally. These discussions often appeared as policy proposals, investment plans, or speeches emphasizing industrial revival. However, the gap between intent and action has remained wide. Hardware manufacturing only reached small-scale mobile phone plants, often decades after neighboring countries had developed robust electronics industries.

The introduction of a Chromebook assembly line isn’t a grand breakthrough but instead a quiet correction in this long-underperforming landscape. It’s not a full-fledged manufacturing hub, and it doesn’t mean Pakistan has joined the global hardware race overnight. Instead, it signals a gradual, meaningful step toward localizing a product category that has been predominantly imported.

This Haripur plant results from an unusual partnership between Google, Tech Valley, Allied, and NRTC. Each partner offers a unique strength: Tech Valley brings digital education programs, Allied offers distribution and operational expertise, NRTC provides government-backed infrastructure, and Google supplies global standards, supply chains, and a long-term presence. This combination underscores the potential for such collaborations to foster industrial growth.

At the launch event, Farhan Qureshi, Google Pakistan’s Country Director, described this project as an extension of Google’s ongoing commitment in the country. He called it the beginning of the “Made in Pakistan Chromebook” journey, illustrating that the initiative signifies more than just a product launch—it’s a stepping stone toward building a local hardware ecosystem.

Pakistan has long awaited such a development. Other nations—Vietnam, Indonesia, India—used early assembly projects as foundational steps to eventually develop component manufacturing and export capabilities. Although the Chromebook line doesn’t fully close this gap, it provides a critical starting point that has been missing for too long.

This modest but important initial step underscores why this moment matters.

Economic implications and the money question

Pakistan’s history with hardware manufacturing has oscillated between optimism and hesitation. Each new announcement sparks hope, yet economic realities often temper expectations. The Chromebook assembly line is part of that complex picture—signaling movement at a time when the country desperately seeks new export markets, but also raising critical questions about scale, competitiveness, and policy clarity.

To better understand this moment, The Express Tribune consulted economist Ammar Habib Khan. His background in applied economics, financial systems, and industrial policy makes him well-equipped to analyze what it takes for Pakistan to establish long-term competitiveness.

“Local device assembly adds value only if it results in exports and enhances the country’s ability to be export-driven,” he explained. “Simply assembling devices here doesn’t automatically bring economic benefits unless it contributes to building an export footprint. Without a clear export strategy, import substitution can lead to higher consumer prices and reduce consumer surplus.”

The focus on import bills is central to this project’s economic significance. Pakistan’s heavy spending on electronics prompts the desire to cut costs, but Habib warned that import substitution alone doesn’t reduce external vulnerabilities. “We need a focused export promotion strategy,” he said. “This enhances competitiveness and drives sustainable industry growth.”

Scale is crucial here. Qureshi from Google mentioned they plan to produce half a million Chromebooks locally. While ambitious, Habib emphasized that numbers aren’t enough—an effective assembly industry requires a supporting ecosystem: plastics for casings, batteries, camera components, and other essential parts. Without this ecosystem at scale, export competitiveness remains elusive.

Nevertheless, such projects do create employment opportunities. NRTC’s operations will generate direct jobs, and supply chain sectors like packaging, logistics, and warehousing may benefit as well. Qureshi highlighted that “The Chromebook project will foster local manufacturing jobs and open new export avenues for Pakistan,” signaling optimism, even as the broader conditions for profound transformation remain uncertain.

The overarching message is clear: If Pakistan aims to be part of a regional electronics manufacturing network, assembly alone isn’t enough. An industry development strategy must swiftly evolve from simple assembly to local component manufacturing with an export focus. The goal should be to serve international markets, not just meet domestic demands.

On a fundamental level, the real significance of this assembly line lies in its potential impact on education. The devices are meant for classrooms, and whether Pakistan’s students benefit depends on more than just the hardware. The future of the country’s tech industry hinges on the quality of digital education, which starts with how effectively these tools are integrated into learning environments.

Chromebooks transforming classrooms

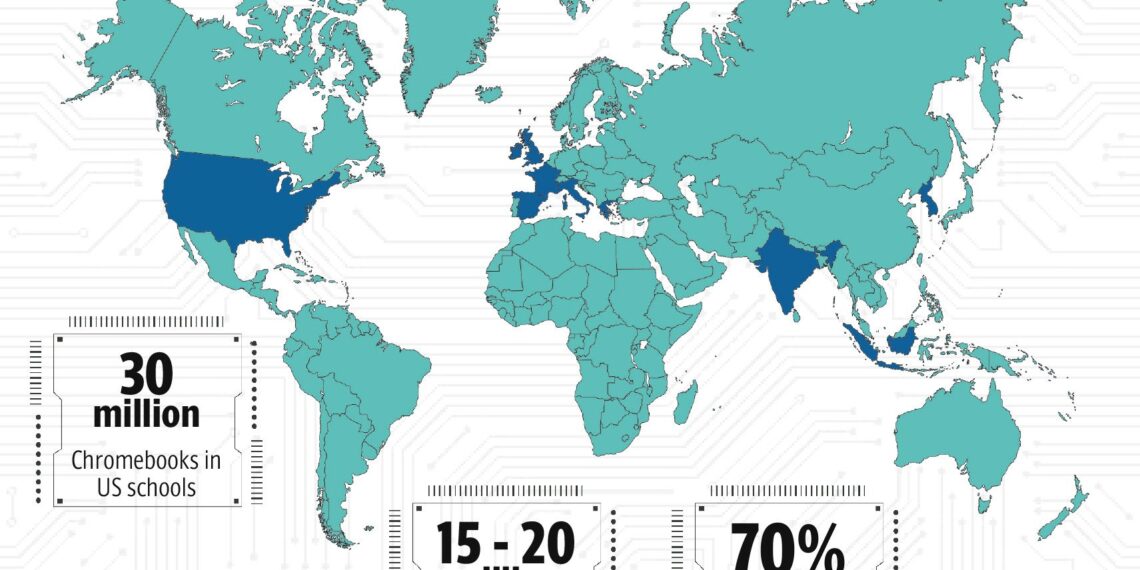

Across the world, educational technology has quietly transitioned from supplemental to essential. Chromebooks are at the core of this shift, favored for their affordability, reliance on cloud-based learning, and low maintenance. For underfunded school systems, they often make the difference between basic digital access and meaningful digital literacy.

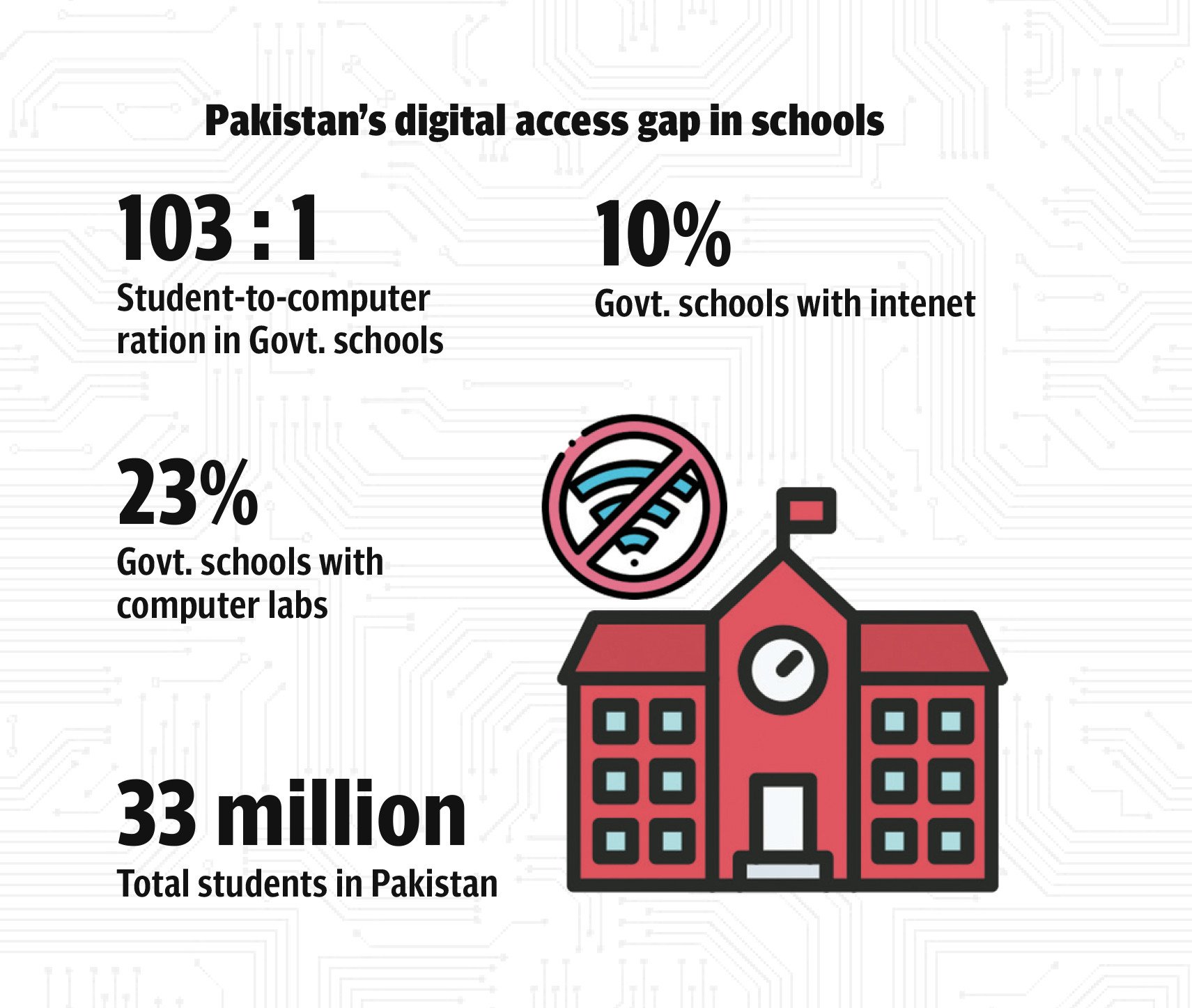

In Pakistan, where many public schools still operate without proper digital infrastructure, the arrival of a local Chromebook assembly line raises broader questions. Can a country where children primarily use mobile phones finally transition to genuine computer skills within the classroom?

This inquiry has motivated Tech Valley’s efforts in recent years. Umar Farooq, CEO of Tech Valley Pakistan and MENA, explained that their initial motivation predates the assembly plant. “Our goal was simple but profound: to make quality, equitable education accessible to every child in Pakistan,” he said. Their approach involved building an ecosystem around available products, fostering adoption and relevance through targeted programs.

Farooq shared insights from Tech Valley’s journey across Pakistan. “From a primary school in Bhakkar/Daddu to university campuses in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, we have seen digital literacy turn students from mere consumers into future creators,” he explained. “This transformation is driven by true Public-Private Partnerships that reach across various levels of education.”

The Chromebook fits into this narrative because it lowers many barriers to digital learning. It’s cheaper than traditional laptops, and its cloud-based system simplifies maintenance for teachers. Tech Valley plans to roll out Chromebook Access Hubs and affordable device-internet bundles to reach Pakistan’s large population of out-of-school children, many of whom have never used computers before.

Imran Ahmed, an expert in educational technology with over a decade of experience, emphasized that hardware alone isn’t enough. “Children who grow up only on mobile phones learn to consume, not create content. Chromebooks introduce typing, coding, and problem-solving—skills Pakistan urgently needs,” he said. However, he also warned that teacher training remains a crucial challenge. “Without properly trained teachers, even the best devices remain underutilized,” he added.

As Tech Valley expands its educational initiatives into the Middle East and positions Pakistan as a regional tech support hub, the question remains: Will the supporting systems be ready? Beyond classrooms, skill-building in training centers, workshops, and factories will determine how far this initiative can go. Supporting the chromebook ecosystem are adults who repair, maintain, and support these devices—building the talent Pakistan needs for sustained growth.

The workforce Pakistan needs

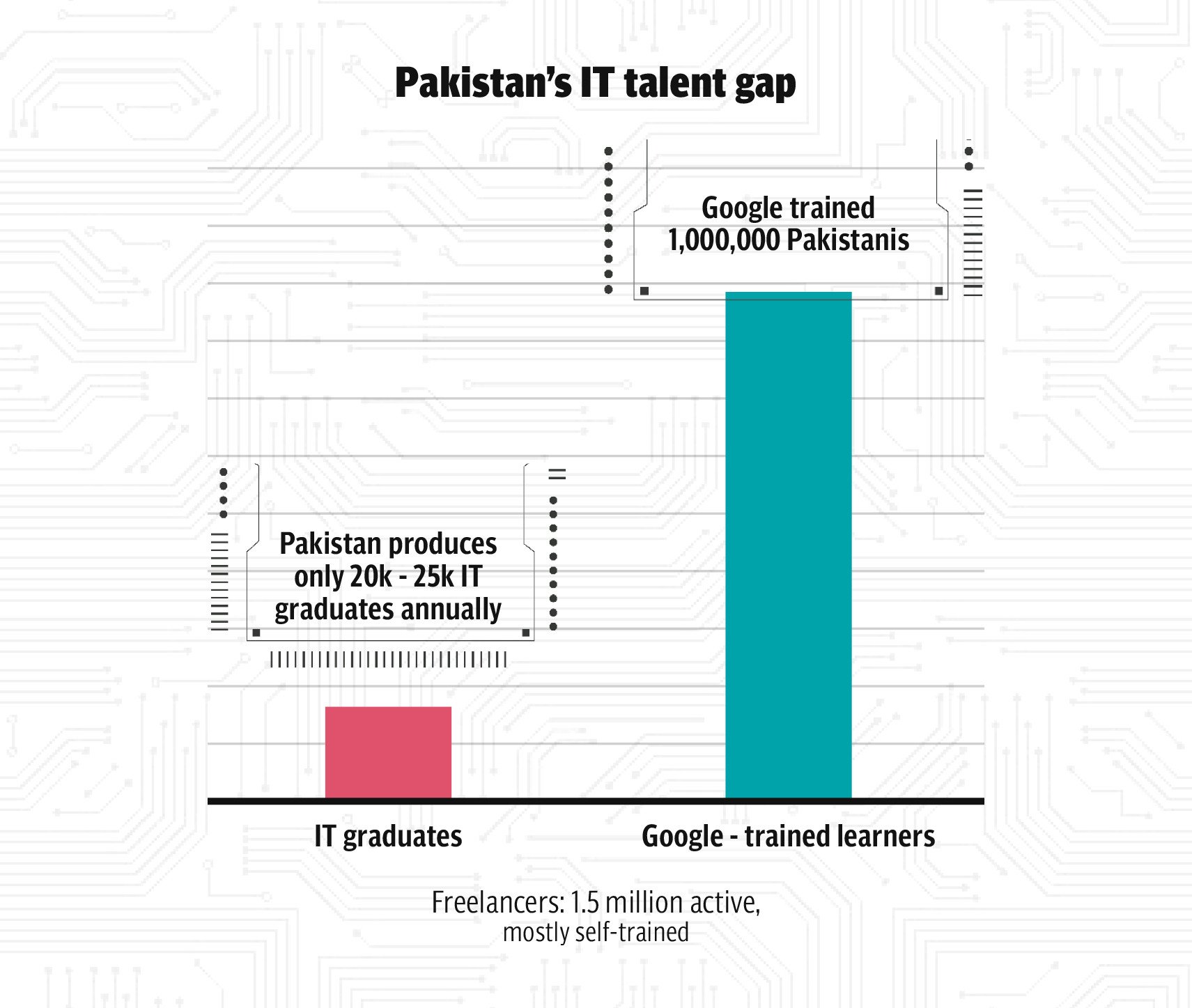

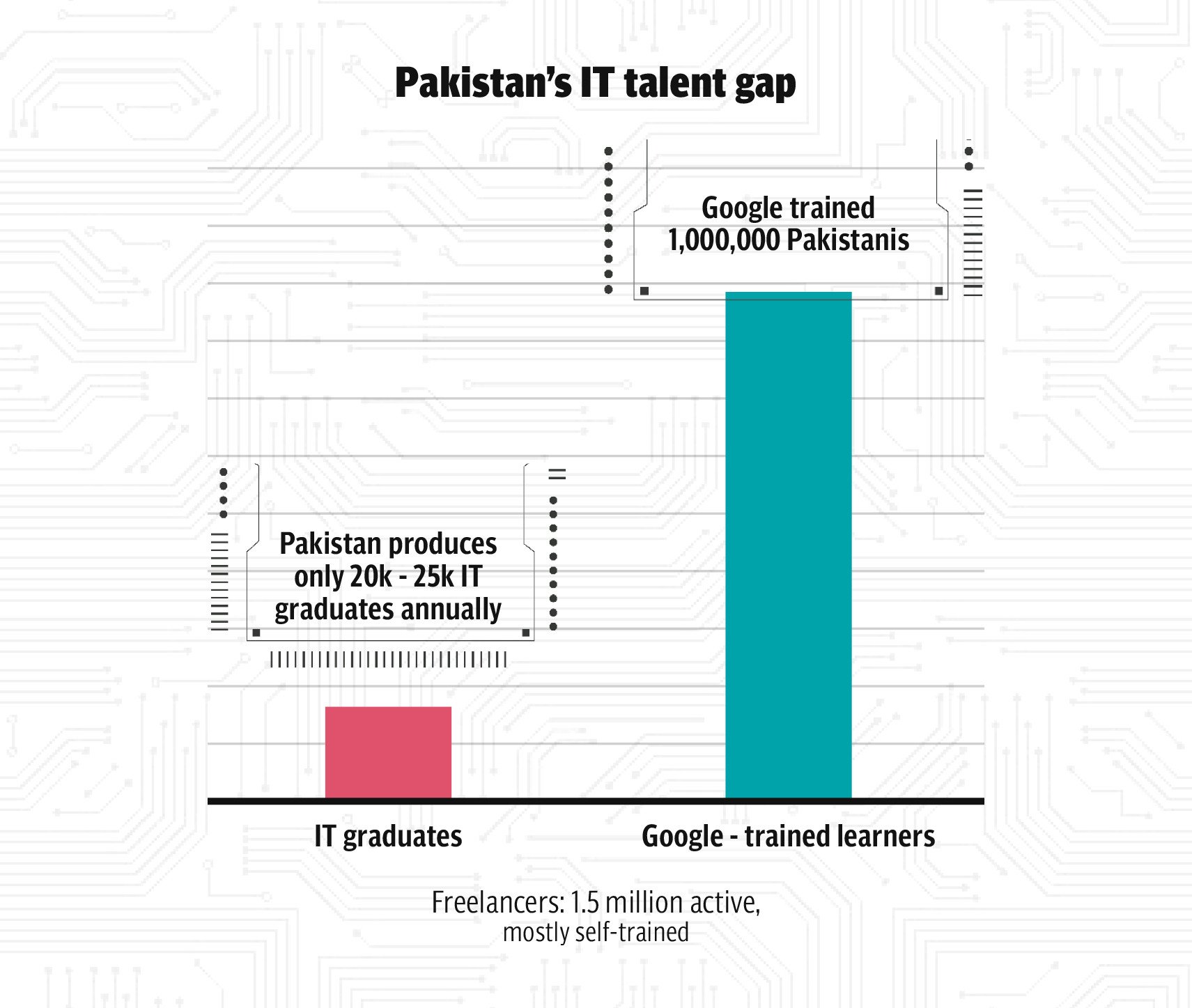

Beyond hardware and economic factors, the Chromebook project spotlights an ongoing challenge: the shortage of skilled workers. For years, discussions centered on software developers and freelancers, but large-scale assembly calls for technicians, repair specialists, quality controllers, and manufacturing supervisors—skills that Pakistan has historically lacked. Without this middle layer, even promising projects depend heavily on imported expertise.

Google’s approach in Pakistan includes this focus. Qureshi mentioned that digital skills development predated the assembly line. “Our primary aim is building skills, because Pakistan’s most valuable digital exports come from its people,” he said. Over the years, Google invested in training programs that have empowered over a million teachers, students, freelancers, developers, and creators with digital know-how.

The recent MoU to train 100,000 developers is a step forward. “We signed an agreement with Pakistan’s Ministry of IT and Telecommunication to expand digital and AI skills, supporting the gaming industry and startups,” Qureshi explained. He linked this effort closely to Pakistan’s broader economic goals, emphasizing that “this partnership will be critical to transforming Pakistan’s digital ecosystem and boosting export-led growth.”

However, the assembly line also creates demand for a different skill set: the technical workforce that maintains manufacturing at scale. This includes repair technicians, quality inspectors, machinery operators, and factory supervisors—skills Pakistan has largely overlooked, despite their importance in a functioning manufacturing economy. Addressing this gap is vital for sustainable growth.

Farooq from Tech Valley highlighted the importance of this layer, stating, “Our vision was to build an ecosystem, not just a product.” He explained that hardware projects cannot succeed on developers alone—they require vocational colleges, certification programs, and training centers, especially in regional and rural areas.

Farooq also noted that Pakistan is beginning to develop domestic capacity to support this system locally and internationally. “We are becoming the regional tech support hub—that’s both a reality and a vision,” he said. If sustained, this shift could generate new categories of jobs—roles that sit between software programming and large-scale manufacturing—and connect Pakistan to global markets more directly.

In this context, talent development and the skills pipeline are central to whether this project is a one-off or the start of a transformative industry. Building a resilient, skilled workforce will determine how far Pakistan can go in leveraging such opportunities, creating a sustainable tech ecosystem rooted in local capacity.

Pakistan’s tech outlook

Every major strategic shift begins with a moment that feels larger than the event itself. For Pakistan, Google’s move to assemble Chromebooks locally symbolizes such a milestone. It signals that a leading global tech company is willing to anchor part of its hardware production in a country that has long struggled to turn potential into tangible results. But symbolism alone is insufficient; what matters is how Pakistan capitalizes on this opportunity.

While the country has long talked about developing a hardware ecosystem, most past efforts failed to reach significant scale. The Chromebook line doesn’t resolve all these issues instantly, but it provides an essential starting point amid a shifting global landscape. As Qureshi noted, “This launch is an inflection point—to set the foundation for the future,” emphasizing that the real importance lies in Pakistan’s entry into a space it has been absent from for too long.

For Pakistan’s youth, the benefits are immediate. A generation of digital natives—many of whom have only experienced freelancing on mobile phones—may now find routes into hardware support, device repair, testing, and cloud-based services with affordable Chromebooks. As hybrid work models grow and hardware demand rises across regions, Pakistan has a chance to position itself as a reliable provider of entry-level devices and the skilled workers to support them.

Long-term success hinges on moving beyond assembly to full manufacturing. And in the end, “Reliability will be Pakistan’s key to exporting,” Farooq said. “Assembly activity alone isn’t enough; we need to develop manufacturing of local components—building an ecosystem that focuses on export markets, not just local needs.” His confidence reflects an ambition to build Pakistan’s reputation, not merely as a device manufacturer but as a recognized global brand.

Risks persist—import restrictions, dollar shortages, regulatory shifts, political instability—all pose challenges to sustained growth. But these hurdles coexist with emerging opportunities: AI integration in devices, regional demand for low-cost hardware, expanding digital education, and a young, eager workforce. The decisive factor is whether Pakistan will seize this moment and build an ecosystem that sustains long-term development.

This Chromebook assembly line signals that Pakistan has a choice: to let the opportunity slip away or to transform it into a foundation for a different kind of tech future—one driven not just by promises but by the people willing to build and sustain it.