Select Language:

PUBLISHED February 8, 2026

KARACHI:

Is your mobile internet running slower than molasses? Over the past year, many users across Pakistan have faced the same frustration. Videos that once loaded instantly now pause for a moment too long. Calls freeze mid-conversation. Refreshing a page takes longer than it should and becomes irritating. It’s not a sudden collapse but a gradual slowdown—something that slips into daily routines unnoticed, until suddenly it’s impossible to ignore.

In Karachi, especially during peak hours, the frustration is evident. Late evenings in Defense and Clifton, lunch breaks in Saddar, and morning commutes around Shahrah-e-Faisal often reveal noticeable drops in speed. Lahore’s Gulberg and Johar Town, Islamabad’s Blue Area and G-10 report similar issues. Signal bars may still appear full, but the experience feels weaker, more stretched out.

Part of this change has quietly emerged since the pandemic. COVID did more than temporarily push work and education online; it permanently changed internet usage. Ride-hailing apps became daily essentials. Small businesses migrated orders and customer engagement to messaging platforms. Payments became digital. Content creation, live streaming, and short-video apps started consuming constant streams of data. Even outside major cities, smartphones have become workplaces, classrooms, and storefronts all in one.

For freelancers, this slowdown has real consequences. Uploads stall. Video calls drop temporarily. Cloud-based tools become unreliable. Students face buffering during classes. Small businesses reliant on social media find themselves retrying actions that once worked flawlessly.

This strain is no longer limited to big cities. In smaller towns and rural areas, mobile internet has become the primary gateway to services, markets, and information. What was once a support tool is now an essential utility, expected to work reliably all the time.

A common concern among users is: the internet used to be better—not necessarily faster, but more reliable and steady under load. The question now is simple: why does a network that once seemed sufficient now feel overwhelmed?

Why 5G alone won’t fix Pakistan’s internet

As frustration grows, a familiar solution is becoming the topic of public debate—launching 5G. Politicians, advertisers, and everyday conversations often see 5G as an easy switch that will make internet faster, smoother, and ready for the future.

This assumption is understandable. Each previous upgrade brought clear benefits. 3G made basic browsing possible. 4G enabled streaming videos and smooth calls. As a result, 5G is seen as the next big leap—an automatic fix for buffering and dropped calls.

But this view is incomplete. It confuses technology with capacity. A new standard doesn’t automatically create more space; it only determines how efficiently that space is used. If the current network is already crowded, upgrading to 5G won’t significantly ease the pressure.

Mobile internet depends on limited radio frequencies. Every streamed video, phone call, ride request, or payment consumes part of that shared pool. When this pool is stretched thin, the network doesn’t fail but degrades: speeds slow down, delays increase, and reliability weakens, especially during busy hours. While newer tech can handle data more efficiently, it cannot create capacity where none exists.

That’s why the promise of 5G often sounds larger than its immediate impact. In many countries, 5G’s most transformative uses require dense infrastructure, compatible devices, and long-term investments. For most users relying on smartphones for work and communication, what’s more urgent is a reliable internet connection that functions consistently.

As discussions about Pakistan’s digital future intensify, industry experts and regulators agree that the problem isn’t the lack of a new technology but the exhaustion of the current infrastructure.

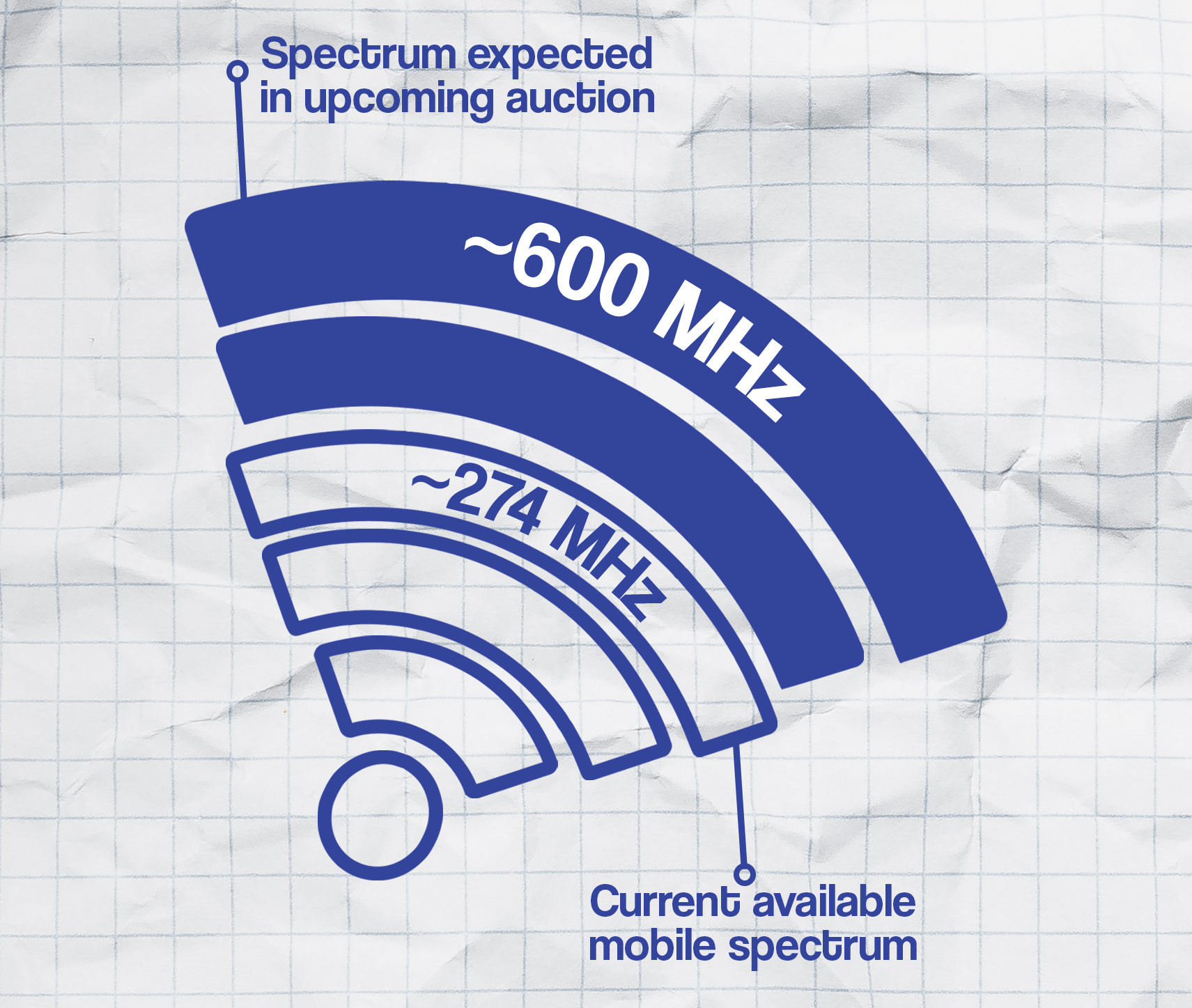

Understanding why mobile internet slows down begins with “spectrum.” In simple terms, spectrum refers to invisible radio frequencies that transmit data between your phone and a nearby tower. Unlike fiber cables, which can be physically expanded, spectrum is finite. Only a limited amount exists, and it must be shared among all users in an area.

When few people are connected, the experience feels smooth. As more join in, that shared space becomes congested. The network doesn’t break; it divides capacity among users, causing individual connections to slow. This is why internet performance dips during peak hours and in densely populated areas. The core issue isn’t just access but whether enough spectrum exists to handle current data demands.

Operator reality: Pakistan has hit the limit

For Pakistan’s mobile operators, the recent slowdown isn’t a surprise. It’s the result of a system stretched beyond its original limits, as one senior executive from a major telecom company explained.

“Think of spectrum as the width of a road,” he said. “If the number of cars keeps increasing, traffic slows down. You can’t ignore that logic. To move more cars smoothly, you need a wider road. What we’ve done here is add more cars without widening the road.”

That analogy captures the fundamental issue: while data usage has surged over the past decade, the available spectrum hasn’t expanded proportionally. As a result, networks are forced to split limited capacity among an increasing number of users—especially in busy urban centers.

He pointed out that this explains why many feel 4G no longer performs as it did. “There’s nothing wrong with 4G technology itself,” he said. “The load has increased dramatically. When thousands of people are streaming, making calls, booking rides, and uploading content simultaneously, the network has no choice but to share bandwidth. People remain connected, but speeds decrease.”

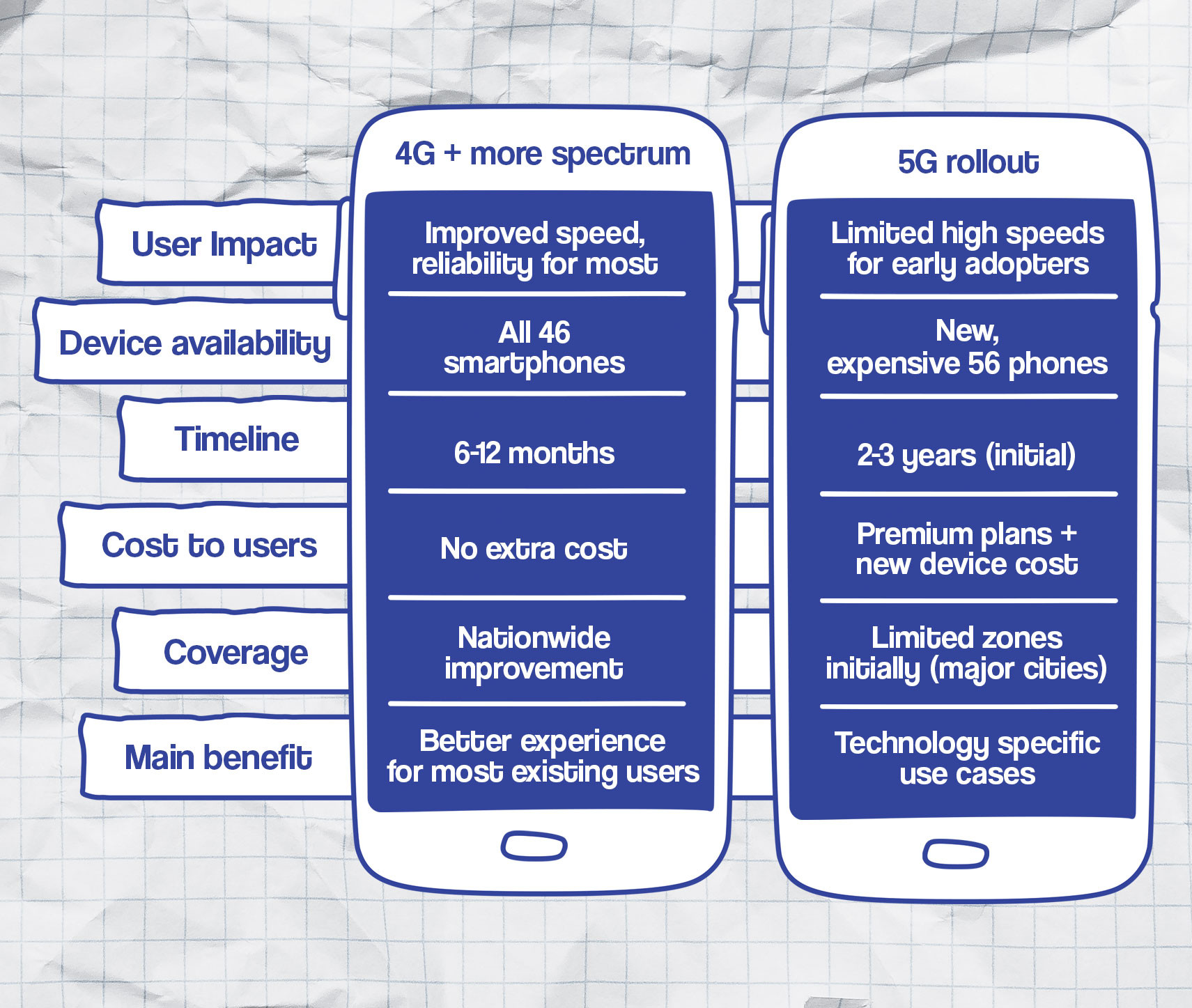

From the industry’s perspective, deploying 5G isn’t an immediate fix without additional spectrum and device compatibility. Rolling out 5G without addressing these issues would benefit only a small percentage—maybe 2-3%—of users, turning it into a premium feature rather than a universal solution.

Financial aspects also matter. Next-generation networks require long-term investments, often with payback periods of five to ten years. In Pakistan, where affordability is limited and compatible 5G devices are costly, returns hinge on device prices falling enough for many to upgrade. “If people can’t afford new devices, they won’t upgrade,” the executive said. “And if users don’t upgrade, operators will hesitate to invest.”

This creates a familiar stalemate: operators hesitate without broader user adoption; users avoid buying new devices without coverage. Breaking this cycle depends on increasing capacity and making devices affordable. Initiatives like handset financing or installment plans could accelerate adoption, but progress remains uneven without such measures.

The immediate focus, he added, should be on practical solutions—expanding spectrum, reducing congestion, and restoring current network performance. Only then can a slow, sustainable transition to 5G happen. “The real test isn’t announcing 5G,” he said. “It’s whether the internet actually works better for everyday users.”

What the industry and regulator agree on

Despite some disagreements, both the industry and regulator concur on the core issue: capacity, not technology, is the main constraint. Both agree that spectrum scarcity has become a structural challenge, and that networks are handling far more data than they were originally designed for, especially in densely populated areas.

Both sides also agree that improving 4G performance is a higher priority than rushing into a nationwide 5G rollout. While they see 5G as inevitable, they acknowledge it’s not a quick fix for everyday connectivity. Device affordability is crucial—no matter how advanced the network, if consumers can’t access it, benefits remain limited. Adoption has to happen gradually.

Finally, both emphasize the importance of long-term investment certainty. Expanding networks needs a stable policy environment. “This isn’t a one-year project,” a senior industry figure said. PTA officials support this, stressing predictable rules and phased obligations to turn new spectrum into sustainable improvements.

Where they differ mainly is in the sequencing and implementation, not understanding of the core problem.

The unresolved questions

Despite consensus on the diagnosis, many questions linger on how quickly these policy plans will translate into improvements on the ground—especially regarding device affordability and implementation speed.

Regulators are confident that the ecosystem will adapt once spectrum is allocated. They expect handset makers to develop affordable models, prices to fall, and supply chains to diversify, leading to greater demand. Historically, demand and supply have gradually realigned with technological shifts.

The industry is more cautious. While device prices are expected to drop eventually, the timeline matters. Without affordable 5G devices arriving soon, adoption will remain limited, weakening the business case for operators to invest heavily. The concern is not whether prices will drop but whether they will do so fast enough to justify ongoing investments.

Implementation also involves challenges—building new infrastructure, sourcing equipment, dealing with regulatory approvals, and ensuring supply chain readiness. Any delays in these areas could slow progress significantly.

Rural areas pose particular challenges. While regulators say coverage will improve nationwide, operators tend to focus initial upgrades where usage and revenue potential are highest—in urban centers. The risk isn’t exclusion but slow expansion, with rural areas trailing behind.

Underlying everything is uncertainty about reliance solely on market forces. Supportive policies, financing options, and device subsidies could accelerate progress, but they are still developing. Without these, Pakistan’s digital progress may be incremental rather than transformative.

What success will actually look like

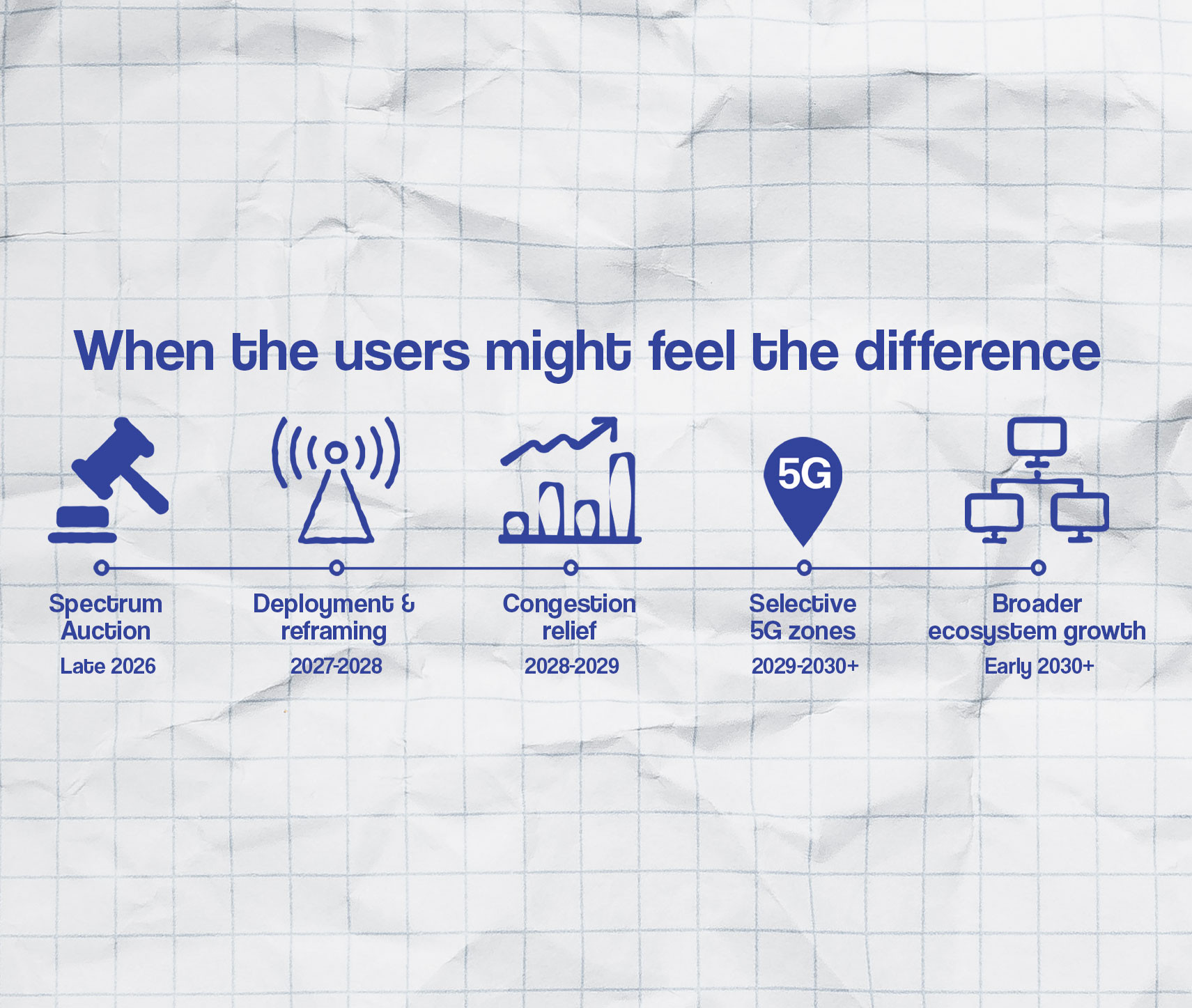

With the spectrum auction scheduled for March 10, 2026, expectations are already rising. However, PTA officials caution that results won’t be immediate. The changes ahead are significant but will take time to realize.

Once spectrum is allocated, networks will need time to order equipment, import hardware, upgrade sites, and integrate new bands. PTA estimates that noticeable improvements should begin within six months—less congestion in busy areas as new infrastructure comes online. Still, these gains will be gradual, not sudden.

“This isn’t an overnight switch,” said Shahzad. “But once spectrum is assigned, operators know where the congestion is. They’ll act quickly because they’re competitive.”

That market competition is key. Early improvements by some will likely push others to follow, creating a cycle of investment rather than a single upgrade. To support this, PTA has adjusted the auction’s financial terms. Unlike before, there won’t be an upfront fee; operators will get a one-year moratorium, followed by phased payments over several years. The aim is to prioritize infrastructure expansion over immediate revenue.

PTA consulted international experts to develop this approach, aiming for a balance between spectrum pricing, rollout goals, and long-term connectivity benefits. The focus is on sustained progress rather than quick wins.

Ultimately, the real measure of success is whether internet quality improves in everyday life—fewer dropped calls, faster uploads, less buffering, and smoother video calls. These everyday experiences matter most because they impact work, study, and daily communication. Better internet isn’t about headlines; it’s about consistent, reliable service that supports economic growth and social connection.